https://whoismap.benkofman.com

Background

When performing OSINT investigations, the Whois service is an invaluable tool in discovering who “owns” a particular IPv4, IPv6, or domain.

For domain lookups, the Whois database tells you the registrar, registration date, and registrant contact information (often times proxied by privacy services and redacted).

IP address lookups will tell you the parent network, the net range organization contact information (if available), and the ISP. The organization contact information often contains an address along with state, province, and country. This information is often what is used by IP geolocation lookup tools such as ipgeolocation.io.

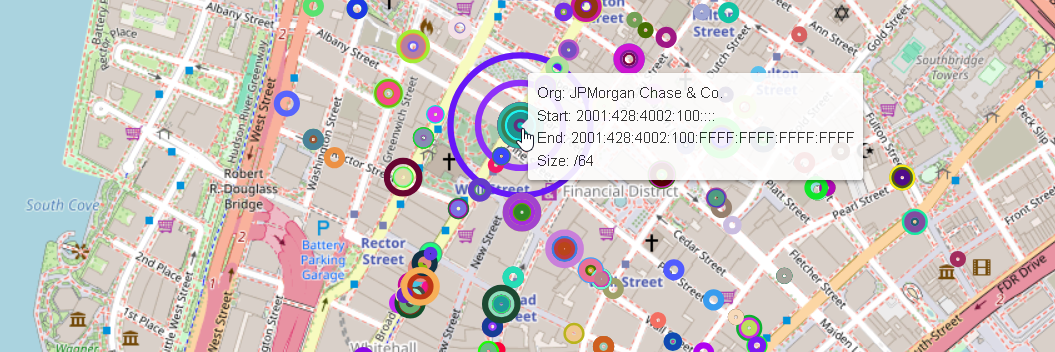

I had the idea to create a geographic visualization of IP address space.

I thought it would be an interesting project to obtain the Whois database, and using the organization address information, attempt to create a somewhat realistic visualization of IP address networks relative to a world map. This might show some interesting takeaways, such as the distribution of IP space in urban vs. rural areas, and the largest companies in a localized area in terms of their dedicated IP space.

There are numerous “maps” of the internet available online but they have a different focus than what I intended to create. Some of the ones I found while researching include the following:

- Map of Broadband Internet Providers in the United States

- Visualization of the most visited sites on the internet

- An artistic geographic representation of the most popular sites

- Hurricane Electric Internet Backbone Map

Design considerations

The map would contain circles that scale relative to the size of the netrange the corresponding organization maintains.

From performing Whois lookups in the past, I knew ahead of time that there would be certain considerations that would need to be addressed. Those include:

- The Whois database is not 100% accurate or up-to-date. This map would represent a point-in-time or cumulative visualization of IP-space, but it cannot be updated in real-time.

- Not all physical addresses for the corresponding IP ranges are accurate. For example:

- ISP residential customers often have an address field containing “Private Address” or “Private Residence”. These cannot be mapped.

- ISP customer networks are often routed using NAT, and their external IP addresses can be a single entry point for a large geographic area. This is why if you plug your own home IP into a geolocation service, it will probably tell you it is located in a general radius within the nearest city.

- Cloud services make up a large percentage of the external IP space. Depending on the cloud provider, the Whois entry for that network may contain the organization and address of the dedicated customer renting that IP space, as opposed to the address of the datacenter itself. For this reason, not all Cloud networks will have accurate addresses.

- The size of the network circles may not be directly related to the total number of addresses. I will need to scale them in such a way that large networks such as an IPv4 /12 (1,048,544 addresses) do not cover too large of a geographic area, making it difficult to see where it’s actually located, even though that network contains exponentially more addresses than say, a /24 network (256 addresses).

Getting access to the raw Whois data

Whois services pull data from the 5 Regional Internet Registries (RIR) - ARIN, AFRINIC, APNIC, LACNIC, and RIPE NCC.

The RIRs each manage the allocation of internet number resources within a specific region, and are themselves allocated ranges of IP addresses from the Internet Assigned Number Authority (IANA).

I browsed all 5 of these RIRs sites to find how I can obtain access to their bulk Whois data. Each registry provides the data of their network ranges free to download from their public FTP servers, but in order to obtain registration data, which contains the physical addresses of each organization, each RIR has its own process for requesting access to their bulk databases.

Most of the RIRs have a simple process of either submitting an online ticket or emailing them a form explaining why you need the data, how you intend to use it, and an acknowledgement of their acceptable use policy, which primarily limits the distribution of the raw data.

The process for LACNIC, which manages Latin America, requires mailing a physical form to an address in Uruguay.

For now, I have only retrieved the data from ARIN, the American Registry for Internet Numbers, which manages allocation of IPs for North American countries. The process was fairly straightforward and is detailed here.

I explained exactly my intentions to create a geographic map of networks, and the request was fulfilled by an ARIN representative within a few days.

Parsing the data

The XML Whois database is fairly straightfoward in how it is organized. The ARIN website states which fields are foreign keys in another type of element.

The raw XML file itself is around 5.7 GB and is composed of:

- asn: Autonomous Systems (~38,000)

- net: Networks (~3.4 mil)

- org: Organizations (~3.3 mil)

- poc: Point-of-contact information for AS or Orgs (~482,000)

The network elements contain subelements called “Netblocks”.

The element associations are summarized as follows:

- asn to its org: asn(orgHandle) = org(handle)

- org to its net: org(handle) = net(orgHandle)

- netblock to net: netblock(netHandle) = net(handle)

Python script to parse Bulk Whois

Because the amount of data was so vast, I used MySQL to store the data which has a much faster write rate than the more convenient but less robust SQLite.

The Python script I wrote first creates tables for asn, net, org, and netblock elements. In hindsight, I should have spent more time minimizing the data type size of each element instead of using VARCHAR(255) for every string. This likely would have sped up the countless queries I had yet to run…

I used the ElementTree XML API library to parse the XML elements and then insert them into the database. Initially, I had the script inserting one element at a time. This was incredibly slow and would have taken several hours.

Instead, I took advantage of the mysql.connector function cursor.executemany, which performs bulk inserts. I saved the element values for each table type in a list of tuples, and when that list reaches 3000 tuples, execute the bulk insert (and empty the list). This reduced the parse script run time to around 20 minutes.

Retrieving coordinates

The most uncertain part of this project was figuring out how to retrieve coordinates from the raw addresses I obtained from the Bulk Whois data (otherwise known as “Geocoding”) without shelling out more than the price of a cup of coffee which is all I was willing to spend.

Before starting this project I assumed I would use the Google Maps API Platform to do this and it would be somewhat straightforward. But, when I checked the pricing, I realized this would not be so simple.

I hadn’t filtered down the networks to map yet, because I wanted to retrieve as much data as I could before figuring out what should be placed on the map. The Geocoding API charges $0.005 for the first 100,000 requests and 0.004 for the next 400,000 (and requires custom pricing over 500,000). Since there are 2.95 million organizations with an address, the total for using the Geocoding API would have came out, at a minimum, to:

0.005 * 100,000 + 0.004 * 2,850,000 = $11,860

Yeah… no thanks. I checked out a bunch of other Geocoding APIs such as well and they ended up having similar pricing models - which are reasonable for individual lookups but unrealistic for a one-time mega batch like my use-case.

Eventually, I stumbled on a page from Texas A&M University’s Geoservices department. They provide their own Geocoding service among other resources, but also maintain a page that list other Geocoding services along with their prices and rate limits. When I first checked this page, it listed the U.S. Census Geocoding service.

This Census site allows for a batch CSV file of 10,000 addresses. I tested it out and lo and behold, after waiting a few minutes for an HTTP response, it returned a file with coordinates for a large majority of the addresses I submitted. There is even a free API that does not require a token, with instructions here.

There was no mention of rate limits for the API, so I gave it a shot. I pulled all the addresses and created 295 CSV files to be used for inputs, limiting each CSV to the 10,000 address limit.

I ran a Bash for-loop uploading all of these CSV files to the Census Geocoding service.

for i in {1..295};

do

curl https://geocoding.geo.census.gov/geocoder/locations/addressbatch --output output/output_file$i.csv \

--form addressFile=@input/input_file$i.0.csv --form benchmark=2020

echo Output file $i retrieved

done

The script took several hours to run since each batch took several minutes for the API to process. I did not want to run multiple requests concurrently out of fear of getting rate-limited. When it finished, I checked the output and was pleased to see coordinates returned for around 70% of addresses I submitted.

Filtering the data

Before writing the front-end code, I needed to determine which networks and their corresponding organization would actually be mapped. I’ll summarize here, but the process took a lot longer than I expected.

What a wanted to do was find every network whose corresponding org’s coordinates are actually where that network infrastructure is located. I ran many queries on the data, cross-referencing the organization addresses and network IPs with actual geolocation lookups, trying to see if I could find any pattern. In the end, I decided that I would need to end up leaving out a large percentage of the networks in the Bulk Whois data.

Some organizations possess a “parentOrgHandle” field in the raw XML data. These organizations are either ISP customer networks or cloud service provider customer networks. The addresses for these organizations did not always correspond to the actual location of the network. For many Cloud networks, the corresponding org address would be that org’s headquarters, even though the Cloud network is actually located in a data center somewhere completely different. Inversely, many of the ISP customer networks were not actually located at the customer’s address, but at the ISP’s office location. I had initially mapped this situation but the number of overlapping circles in one spot often crashed the browser tab (a couple of these somehow still made it onto the final graph).

After I decided on the networks I wanted to map, I created a python script to generate a JSON file that contains all the mapping data. The final SQL query to pull the data is as follows:

SELECT

net.version,

org.name,

netblock.startAddress,

netblock.endAddress,

netblock.cidrLength,

locations.coordinates

from net

INNER JOIN netblock ON net.handle = netblock.netHandle

INNER JOIN locations ON net.orgHandle = locations.orgHandle

INNER JOIN org ON net.orgHandle = org.handle

where net.orgHandle

not in -- Not an ISP/CSP

(

SELECT

parentOrgHandle

from org

)

and org.parentOrgHandle = "" -- Not an ISP/CSP customer organization

and locations.coordinates != ""

and org.handle != "IANA"

and coordinates

While the networks that made it onto the map obviously represent a small portion of the total IP space without any cloud or ISP networks, they are, for the most part, in their actual geolocation.

Mapping the data

The JavaScript mapping library I used is Leaflet, a super popular library with over 40k stars on GitHub.

JavaScript file for mapping the data

This library is very easy to use. Each network in the JSON file would be represented as a Leaflet Circle with a radius that scales exponentially depending on the CIDR length.

I used Desmos to create two separate exponential functions for IPv4 and IPv6 by specifying the upper and lower bounds of the radius I wanted rendered on the map. In hindsight, I can probably make the radii a bit larger because many of the large networks (like /16 IPv4 and up) don’t look that much bigger than the smaller networks.

My initial idea was to create an API to retrieve the organization data (name, address range) when a user clicks on a circle, but instead I decided to just download the entire JSON file into the browser. I did this using the IndexedDB API, which allows for client-side structured storage of large amounts of data.

After rendering every circle on the map, the browser tab slows down signficantly and becomes partially unresponsive. To mitigate this issue, I implemented the Leaflet plugin MarkerCluster, which produces the clusters of markers you see when the map is zoomed out. After zooming in to a smaller area, the cluster disappears and all the circles/networks in the area appear.

Deploying to production

Since the final app is all front-end code (JavaScript, HTML, CSS), this made deployment incredibly easy. I was adding the JSON file to an AWS S3 bucket when I noticed S3 buckets can be configured as static websites.

I just followed the docs for hosting a static website on Amazon S3. All I really needed to do was upload all the files, verify ownership of my domain on my DNS provider (Cloudflare), add a CNAME record for the “whoismap” subdomain, and I was good to go. The setup page handled generating certificates to enable HTTPS, as well as a few other minor configurations.

Conclusion

This was an interesting project and at the very least I learned some things while doing it.

If I ever want to map the rest of the world’s IP space, I’ll need to get access to the other RIRs’ Whois databases, and figure out another cheap way to Geocode all those addresses too, since the US census won’t have them.

Screenshots

Seattle

San Francisco

Washington D.C.