Introduction

Smartphones constitute the largest digital attack surface in modern society - over half the global population and most people in the developed world own one. Mobile applications are heavily relied on for everything we do, be it communication, banking, media, navigation, photos, etc. The average person spends four to five hours a day using their phone. They are a part of us. We are cyborgs without a physical link between our mechanical and biological components (for now).

The two dominant platforms are Android and iOS. Combined, 99.5% of smartphones run either operating system - most app developers support no other legitimate choices. Android dominates the global market share at about 73.5%, with iOS at 26%.

This article will explore the two platforms’ primary distinctions and compare their native attack surfaces. Mobile security is a broad field; this article will not cover cellular network security or other adjacent systems like cloud backup services. We will evaluate whether devices running either operating system are more likely to be compromised depending on the user’s risk profile. Vulnerabilities in mobile applications will also not be discussed, as this is a separate topic standardized by the OWASP Mobile Application Security Verification Standard (MASVS) and other resources and is mainly a responsibility of application developers.

The Smartphone Market

For Americans, it may be a surprise that iOS only makes up about a quarter of the global smartphone market share, as previously stated. Apple controls more than half of the market share in America. Because only one company produces both the phones and software, it creates the perception that iPhones are the dominant product. iOS is the largest smartphone manufacturer in the world, but again, it only controls a quarter of the total market share.

Unlike iOS, the market for Android phones is a fragmented ecosystem with many device manufacturers. As of January 2025, Google recognizes 58 companies as official Android device manufacturers listed on the Android Enterprise website. The four leading manufacturers worldwide are Samsung, Xiaomi, Vivo, and Oppo as of January 2025.

In the United States, Samsung and Google Pixel lead the Android device market. Google Pixel is the only device that uses the stock Android OS since Google also maintains the Android Open Source Project (AOSP). Most other OEMs add additional features and modifications to the Android OS. Some manufacturers have changed Android so much that they market brand-new operating systems, like Xiaomi’s HyperOS, Vivo’s Funtouch OS, and Oppo’s ColorOS.

Some organizations build devices running Android for purposes other than personal phones, such as Honeywell, which has an entire line of “Mobile Handheld Computers” made for industrial use cases. The diversity in the Android device marketplace leads to an important risk factor of mobile operating systems - software update consistency and timeliness.

Security Patching

iOS Architecture

iOS has a monolithic architecture, and Apple builds most major components across the software and hardware. The operating system is composed of the following layers starting from the lowest level:

- Core OS: Kernel, chip drivers, cryptographic operations

- Core Services: Includes basic functionality like cloud data transfer, location services, file system access

- Media: Handles graphics and audio rendering and processing

- Cocoa Touch: API providing access to hardware and software features like user interface elements or the camera

Because Apple controls the entire tech stack of its products, its update process is very streamlined. Since iOS 16.4.1, Apple also implemented Rapid Security Responses to quietly push critical bug fixes between standard iOS updates. You can view the complete list of security updates for all Apple products on a single page on the Apple website.

Android Architecture

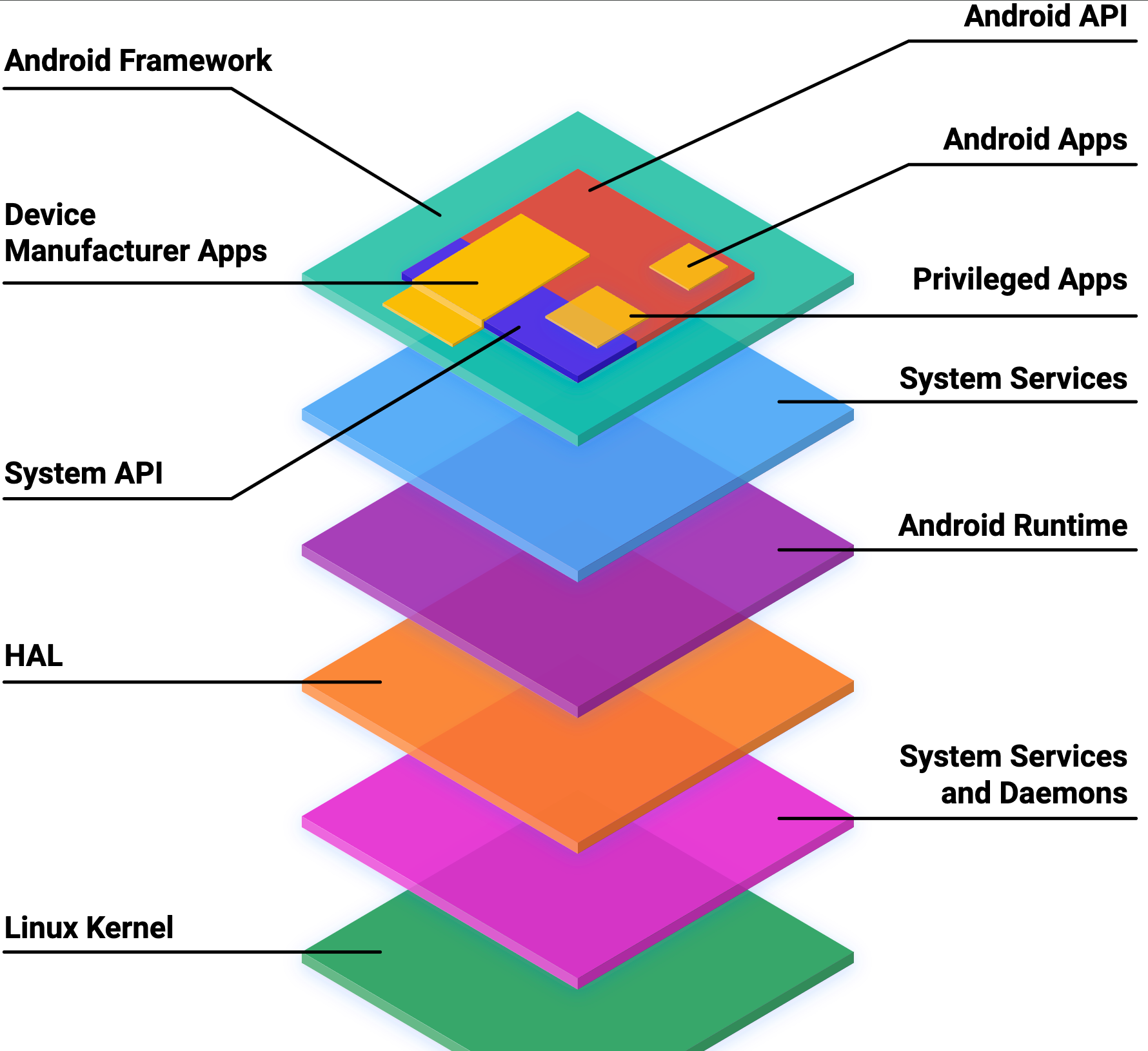

The security update process for Android is not as simple. The platform is composed of several layers, each managed by different entities.

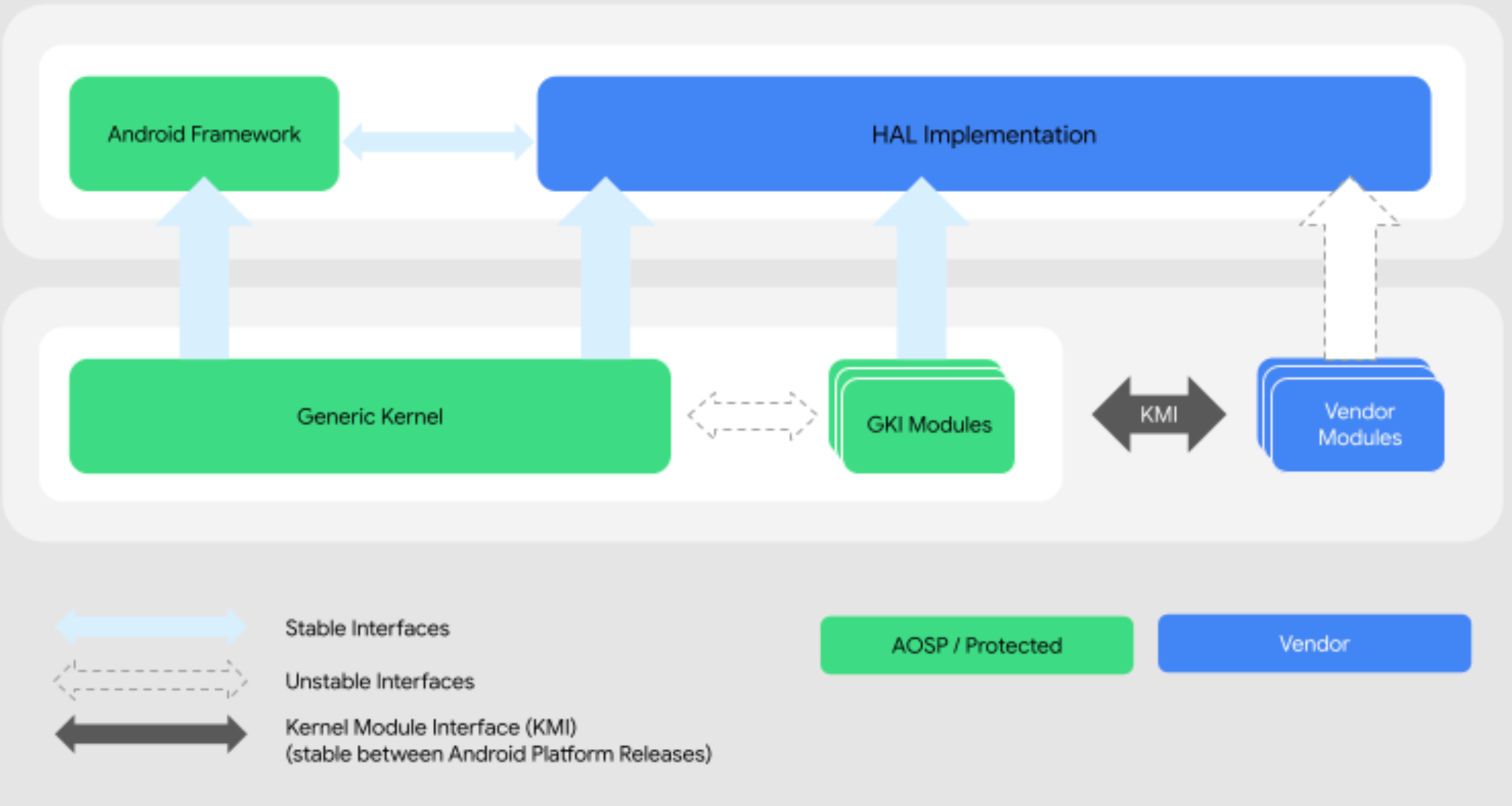

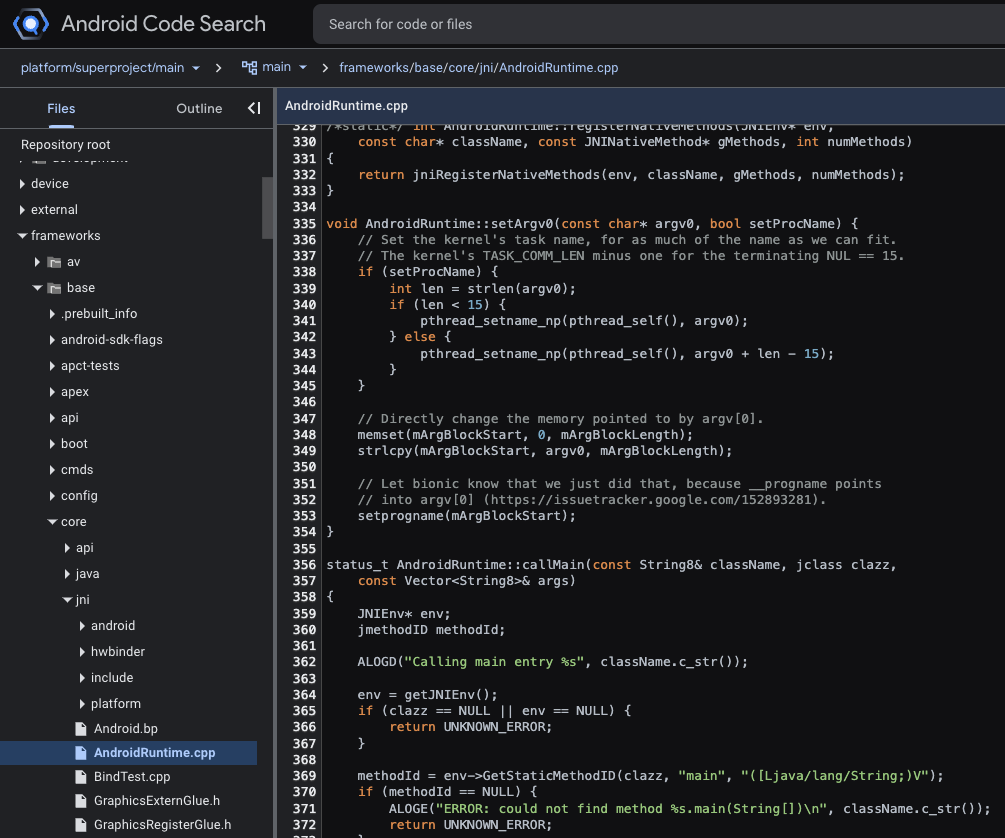

The AOSP builds on the Linux kernel to form the Android Common Kernel (ACK), which Generic Kernel Image (GKI) modules extend to be hardware-agnostic. Hardware vendors implement device drivers using the Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) Interface Definition Language (HIDL) so the operating system can control chips, cameras, microphones, etc.

Applications run in the Android Runtime (ART) virtual machine, which compiles Java byte code to native machine code and acts as a wall between the application and the operating system. The Android Framework defines higher-level Java APIs like the user interface, location services, and inter-app communication protocols.

OEM Customization

OEMs often customize every layer of the Android stack to add their proprietary features. To ensure consumers can only use a specific carrier, the OEM adds tweaks for devices sold through the carrier, like restricting the SIM card or the bootloader to prevent users from flashing custom ROMs. The operating system is often modified to gain a competitive advantage over other manufacturers. For example, Samsung has developed some additional capabilities into the Android OS that they release with their devices, such as:

- One UI: A custom user interface that builds on the Android Framework that provides more modification and accessibility controls.

- Integration with Samsung devices like the S-Pen - requiring additional HAL drivers and Android Framework components.

- Samsung Knox: A security platform that secures every layer of the Android stack, similar to endpoint detection and response (EDR).

- System level apps: Samsung installs its own default apps like the Samsung Internet browser, Notes, Pay, Health, and the Galaxy Store.

When a vulnerability is discovered and fixed in the AOSP, OEMs may take months to implement the fix, as it must be modified to fit the specific vendor’s implementation. Cellular carriers may also need to test the updates to ensure they are compatible with their networks, contributing to the release delay.

Because manufacturers customize the stock AOSP so much, patch consistency is highly variable among OEMs. A 2024 research paper on Android Security Updates published by Google (so take it with a grain of salt) analyzed patch consistency among the top Android device vendors. They found that Xiaomi and Oppo generally release quarterly rather than monthly patches and have shorter support periods. Samsung releases monthly updates for newer models but slows over time. Google Pixel releases security patches monthly throughout their device lifespans, regardless of region, and generally has the longest support periods.

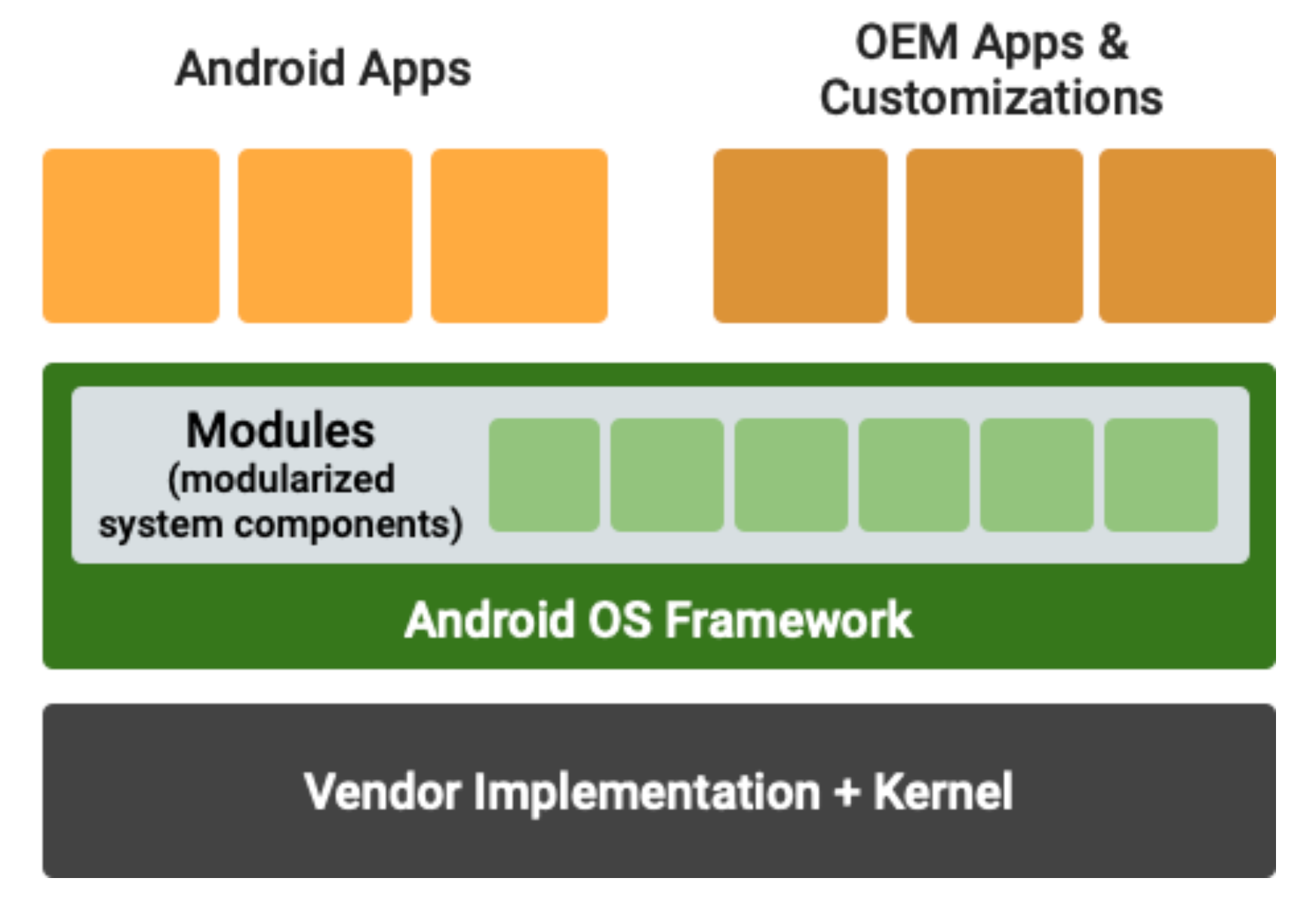

Project Mainline

The Mainline project aims to address this issue. Starting with Project Treble, the Android Framework divided some of its major components into modules to apply updates outside regular Android version releases. Mainline extended this to include critical components like Bluetooth, Media Codecs, Network Stack, Permission Controller, and Wi-Fi, which are often the target of network-based exploits.

Devices must have Google Mobile Services (GMS) enabled to receive Mainline updates as updates are released via the Play Store. GMS allows Android devices to use Google applications like the Play Store, Gmail, YouTube, Chrome, etc. However, GMS is banned in China. Android devices sold in China rely entirely on OEM updates for patching, but they most likely have built-in backdoors anyway.

Project Mainline is not a comprehensive solution, and many security bugs discovered in Android affect system components that Google Play system updates do not cover. Also, the Mainline updates only include the “partial security patch level (SPL)” published in the monthly Android Security Bulletins. The complete SPL includes CVEs identified in proprietary hardware components like Qualcomm and MediaTek chips in many Android devices. Google Pixel is the only vendor that includes the complete SPL in each month’s update.

Vulnerability Research

So, iOS seems generally more reliable regarding timely security patches. But that doesn’t answer a crucial question - which platform is more likely to be exploited? Specifically, by advanced attacks that require limited interaction from the user or physical access to the device - the kind a security-conscious user can do nothing to prevent? We can only look at historical data and make an educated guess to determine this.

One thing is sure - both platforms are riddled with security bugs. This has nothing to do with the quality of the engineers building the platforms; they are world-class. It’s simply a result of the size and rate of change of the codebases. Both are extremely mature platforms that are constantly being improved. Even if a product has a small defect density (number of bugs per line of code), as the codebase grows, so does the number of bugs.

Research Accessibility

iOS has a very high barrier to entry for security research. Like most major organizations, Apple has a bug bounty program and pays big bounties for flaws found in its products. It has also implemented the Security Research Device Program, which provides researchers with a modified device that allows privileged access to the OS. However, this program is very restricted and has limited application windows.

Jailbreaking the latest iOS is very difficult for the general research community, and the latest versions rarely have a working jailbreak publicly available. Although a jailbreak is a major security flaw, it makes it easier for researchers to find other issues. Corellium is a virtual mobile device platform researchers can use to analyze a jailbroken version of the latest iOS, but the emulators are still not the ideal environment. Corellium devices are reverse-engineered versions of iOS, and some features like iMessage and phone calls do not work. Finally, iOS is proprietary - no one can access the iOS source code except for Apple employees.

Conversely, Android is completely open source. The only software on an Android device that isn’t open source is OEM drivers (and other OEM modifications), Google Mobile Services, and applications. Anyone can view the source code on Android Code Search, which includes all levels of the OS from the kernel to the Android Runtime. Users can easily root many off-the-shelf Android phones, allowing more visibility into the device’s internals. Rooting makes vulnerability research very accessible to anyone with the skills and drive to find bugs in Android. Finding major bugs in Android is still very difficult. However, anyone who has done white-box or black-box product security testing understands how much faster you can identify security issues with source code.

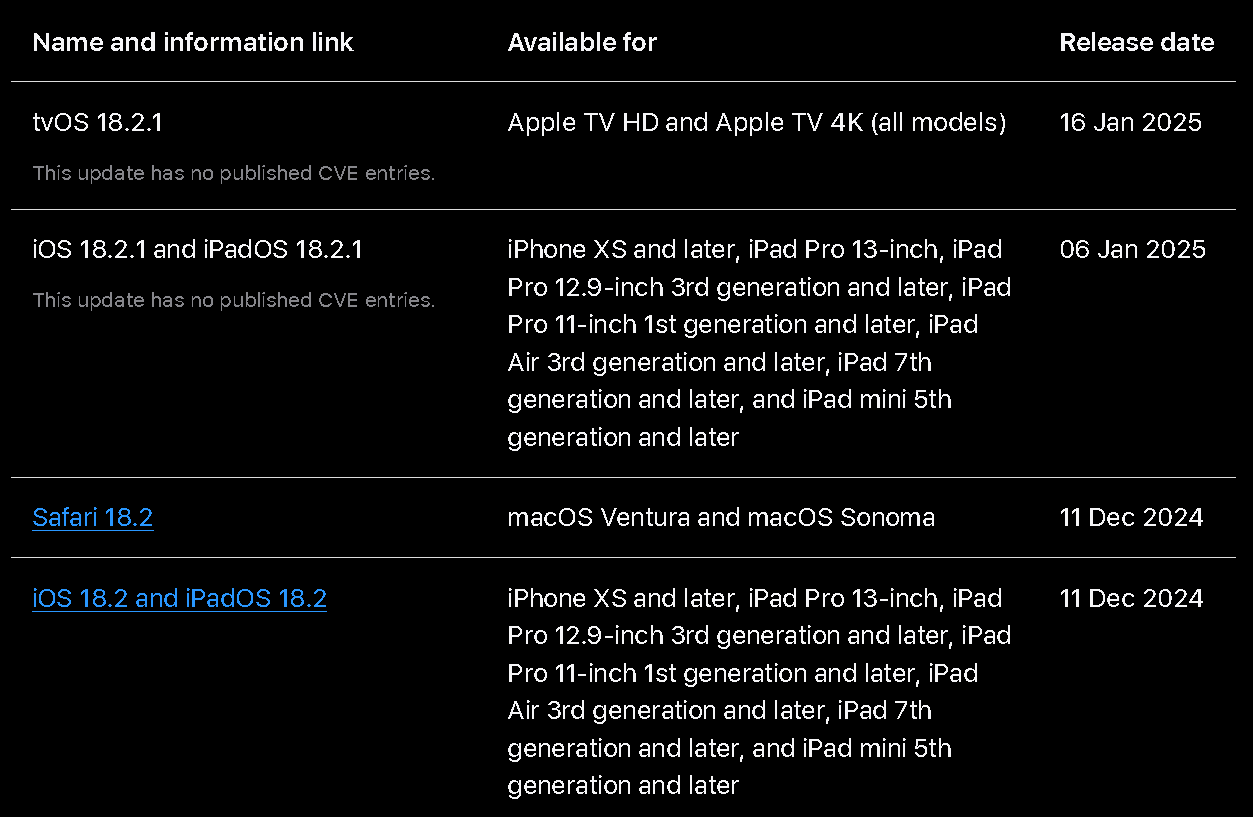

Security Bulletins

We can draw some conclusions by comparing recent security bulletins from Apple and AOSP. The Apple security update issued on January 27th, 2025, for iOS 18.3 included 27 CVEs across different iOS components like AirPlay, WebKit, CoreAudio, and others. The previous security update for iOS was released on December 11th, 2024, for iOS 18.2, which included 36 CVEs affecting Apple software. This update follows the previous update released on November 19th, 2024, together making up about two months of updates.

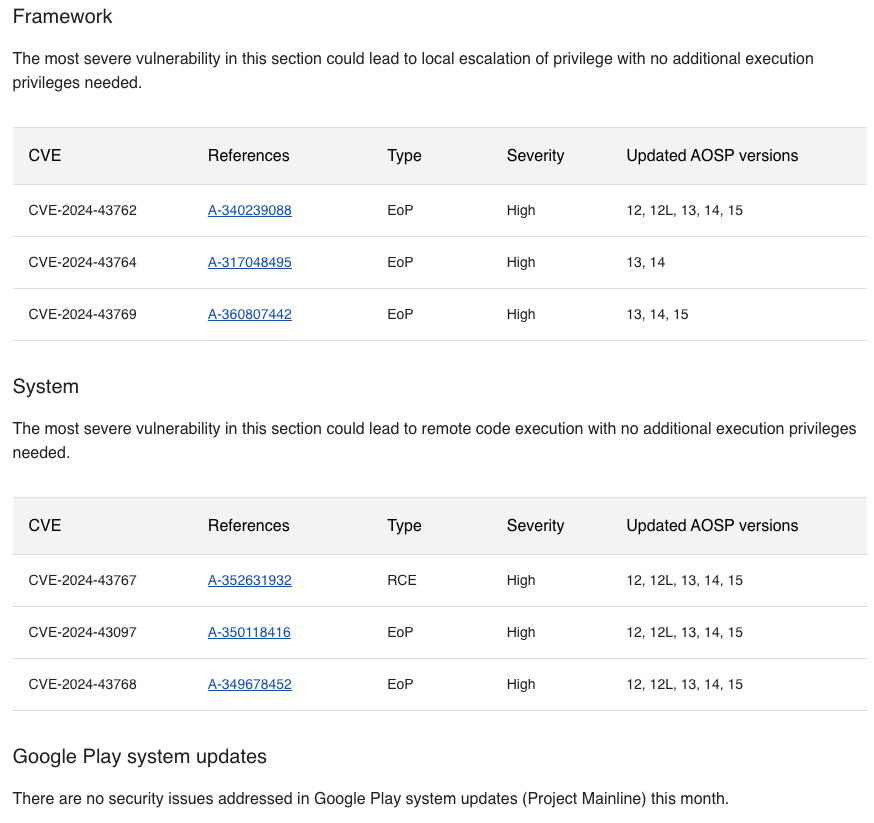

The January 2025 Android security bulletin covers 26 CVEs affecting the most recent AOSP versions (12 through 15) discovered during December 2024. The majority of these affect the core Android system and framework components. Only two vulnerabilities are for Project Mainline modules, specifically the Documents UI and Permission Controller. The December 2024 bulletin, covering bugs found in November, includes only 6 CVEs in the AOSP.

Of course, two months of data is nothing compared to the entire history of these platforms. However, we can learn about the general nature of the security updates. The number of disclosed CVEs does not necessarily indicate a more vulnerable platform or robust vulnerability discovery program. I predict iOS will have far more CVEs than Android since Apple built the operating system from scratch, along with many additional features to allow iPhones to interoperate with other Apple products more easily (and make it more challenging to switch to Android).

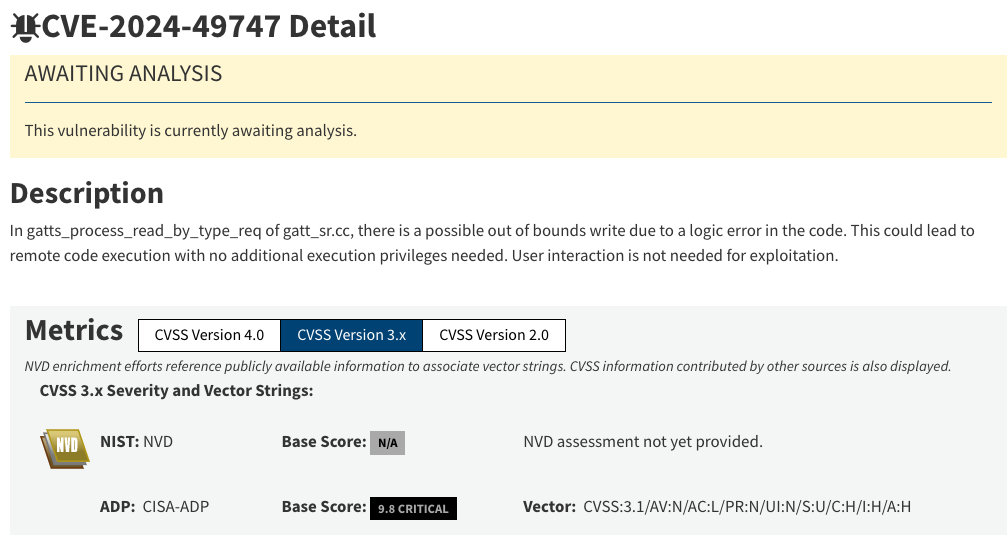

What is noticeable about the advisories is the severity of the bugs fixed in the updates. The Android security bulletins include, at a minimum, high-severity bugs, mainly relating to privilege escalation and remote code execution. The January 2025 bulletin includes five “critical” severity issues according to the AOSP, with CVSS scores mainly in the high eights since the bugs are primarily exploitable over the local IP network instead of wide area network delivery methods like SMS and phone calls.

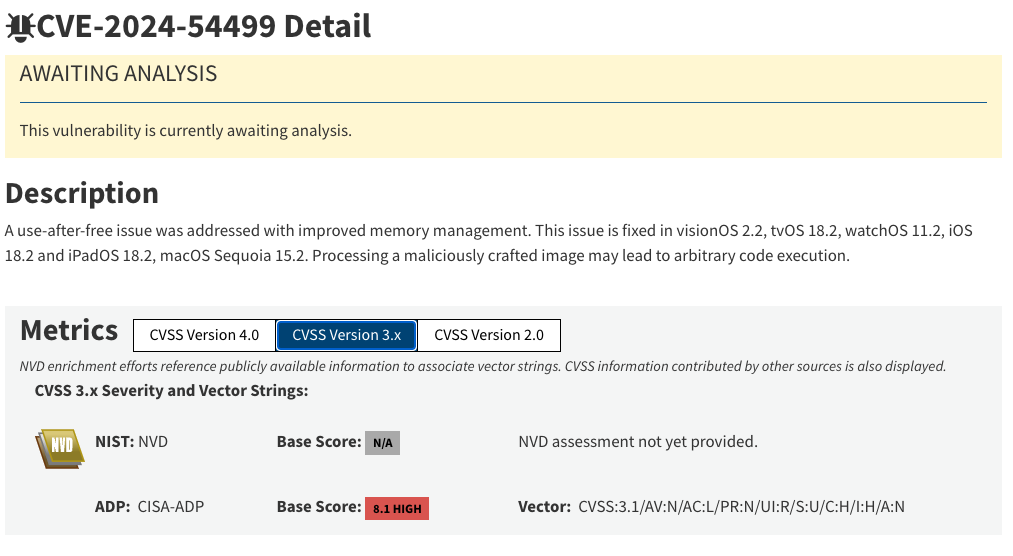

The iOS security updates include bugs that are generally less severe. The majority of them are related to unexpected app termination or denial-of-service, with many requiring user interaction or physical device access, equating to mainly medium-level CVSS scores. There are a few arbitrary code execution bugs, which also require user interaction, diminishing their severity.

CVSS scores alone don’t paint the complete picture. A vulnerability may be critical according to its CVSS score but only exploitable under particular conditions and with limited reliability, reducing its risk. Attacks from APTs and other sophisticated threat actors often combine several zero-days to gain full device control. The average severity of the issues regularly fixed in Android compared to iOS may reduce the likelihood of logical attack vectors being available to attackers targeting Android with zero or one-click exploits. Without being an APT and having an arsenal of zero-days, we can only look at previous attacks on mobile devices to ascertain which operating system is more susceptible to advanced threats.

Exploit History

As we will see, the Android malware ecosystem is far more virulent than iOS since, like a PC, there are fewer limitations on which applications can be installed. However, which platform has been the subject of more advanced zero-click attacks?

iOS Hacks

It’s fairly well known that iOS has long been the target of Pegasus spyware developed by NSO Group. Exploits such as KISMET, FORCEDENTRY, and BLASTPASS have been giving NSO Group customers access to their targets’ iPhones for several years by exploiting attack vectors like iMessage, Safari links, Find My, and other native iOS features. There are countless articles about these attacks, and they don’t seem to be slowing down anytime soon. Citizen Lab has been tracking Pegasus for years and regularly releases reports on Pegasus targets and technical details.

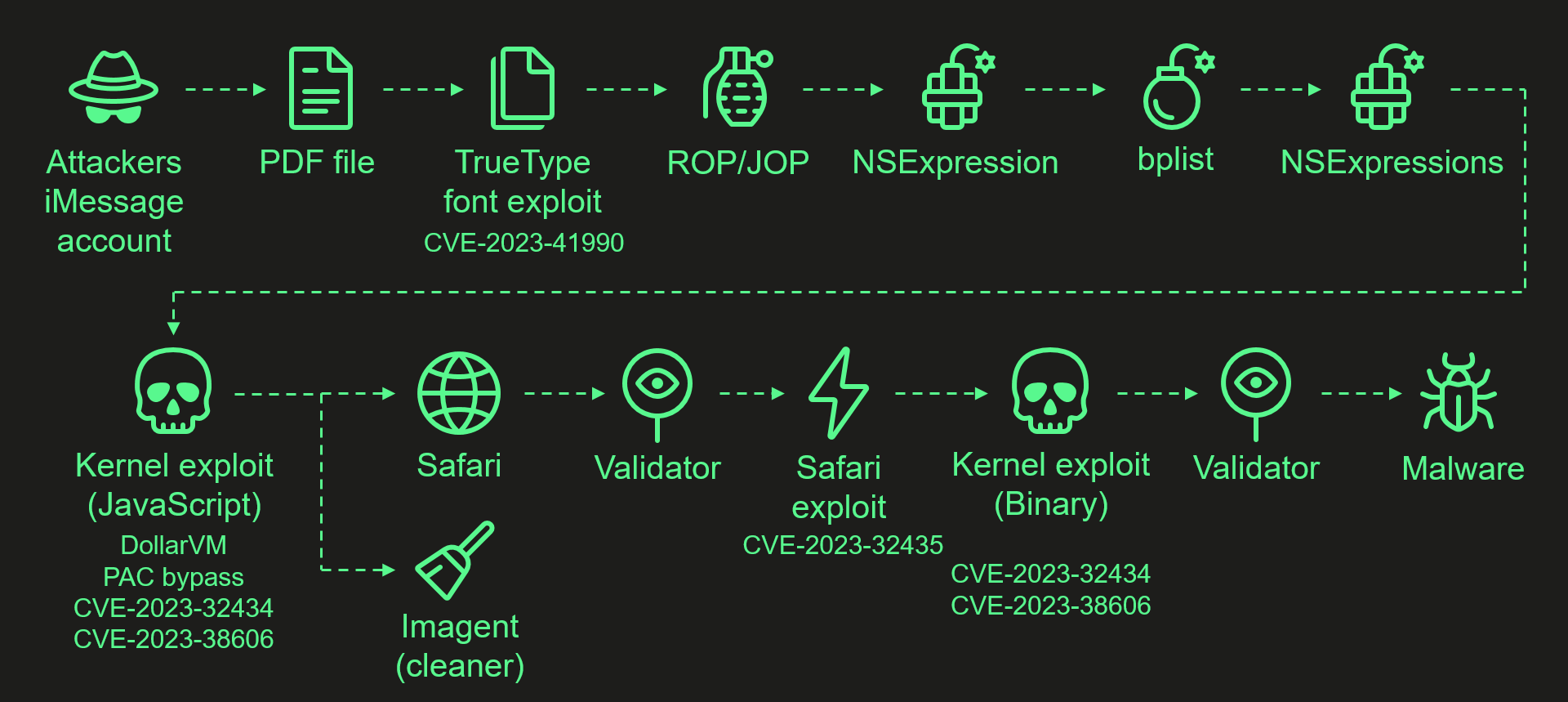

In 2023, Kaspersky researchers discovered a sophisticated iOS hacking campaign they dubbed “Operation Triangulation” targeting mainly Russian citizens and officials. The malware, called “TriangleDB”, was (again) delivered via malicious iMessage attachments, and included a series of four zero-days to achieve full device compromise.

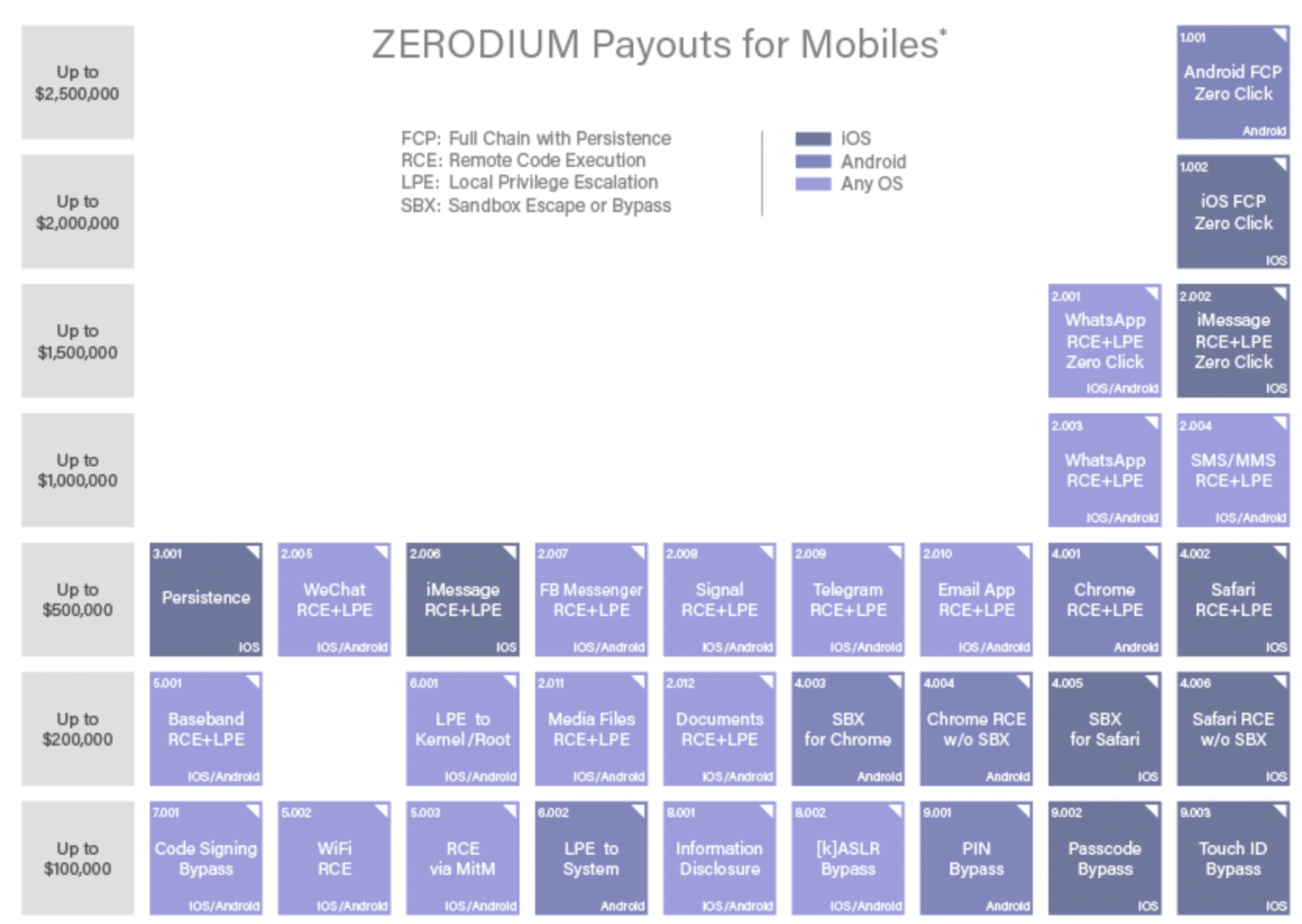

Apple has created additional security measures around iMessage, such as BlastDoor, which Apple vaguely describes as additional sandboxing and memory protection. Time will tell if iOS continues to fall victim to more spyware. Also, iOS full device compromises have been historically cheaper than Android on the zero-day black market. While zero-day prices are, obviously, not as accurately measured as the S&P 500, zero-day brokers like Zerodium (which closed down in 2024) have advertised higher bounties for Android Full Compromise with Persistence (FCP) packages than iOS.

Android Hacks

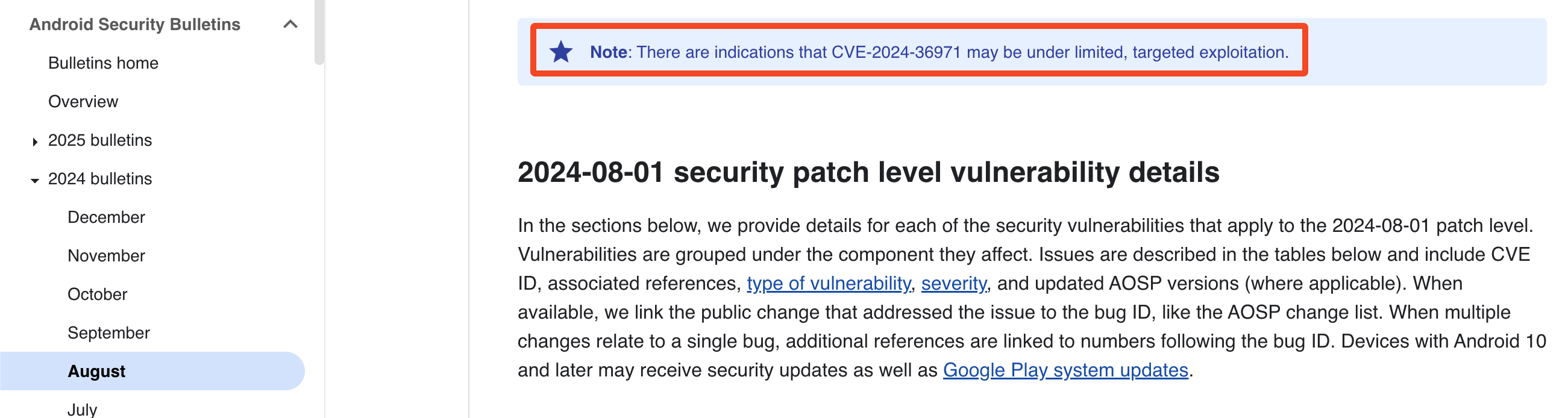

Android zero-click exploits appear less common in the wild than iOS, but they still exist. As we have seen, plenty of remote code execution bugs are found in the AOSP, such as CVE-2024-49415, can be exploited by a crafted RCS message sent on Google Messages. Occasionally, Android security bulletins will also advise whether some CVEs are under active exploitation in the wild, such as in the August 2024 bulletin (although Google has provided few additional details).

WhatsApp vulnerabilities like CVE-2019-3568 have been used to install spyware on iOS and Android. The vulnerability is a buffer overflow affecting native code in WhatsApp’s VOIP stack. It’s unclear how reliable these types of application-level exploits are against Android. They most likely need pairing with other Java-based attacks to escape the Android Runtime sandbox, such as type confusion, object corruption, or insecure deserialization.

One thing to note is that hardware supply chain vulnerabilities may also affect Android devices. Recently, Serbian activists’ phones were hacked using the Cellebrite Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED), another Israeli-developed mobile exploitation tool marketed for law enforcement and government agencies (that the company deems ethical). The UEFD gives attackers root access without needing the passcode but requires physical access to the device.

One Serbian journalist, who the Serbian police arrested for allegedly driving under the influence, suspected his phone was tampered with while detained and provided it to Amnesty International (a human rights NGO that also performs security research) to analyze the device. In coordination with Google Project Zero and Threat Analysis Group, Amnesty International determined Cellebrite UEFD was exploiting vulnerabilities in a Qualcomm chip driver used in the journalist’s Xiaomi device. The researchers found NoviSpy malware on the device, likely installed after gaining root access using the Cellebrite tool. The Serbian government needing physical access to the activists’ devices could indicate the lack of availability of remote zero-click exploit packages targeting Android. Amnesty International has since released a guide for detecting NoviSpy on Android devices.

Common Malware

Nation-states likely have more difficulty gaining covert remote access to a fully patched Android device than iPhones. But what about less reliable attacks like malicious applications delivered via phishing or app stores? Compared to iOS, Android is undoubtedly like the Wild West. Run-of-the-mill malware strains run rampant, and if users are not careful, their devices can easily get infected.

Android Malware

For Android to install an application, it must be self-signed by the developer. That’s it. This protection is only to prevent existing apps with the same package name from being overwritten, like during application updates, not to verify the developer’s identity. For this reason, many fake versions of popular applications share the same name as the legitimate version. As long as a device has not already installed the legitimate version, users could install the fake version, potentially log in with their credentials, and have them compromised. Sketchy sources selling cheaper phones may preload them with malware and fake versions of popular applications.

APK files contain the Android application bundle. These files can be exchanged via any communication medium, such as email, text, instant messaging, websites, etc., and installed directly from the downloads folder. Third-party app stores also exist and do little to nothing to filter out malware and scams. Many well-known Android malware strains propagate using these methods and engage in all sorts of nastiness, such as infostealing, cryptomining, and banking theft. However, in addition to first being installed by the user, the application often needs to request additional permissions to perform its tasks. Below are the three major permissions categories, along with some examples:

- Normal: Granted automatically and doesn’t have any significant security concern

- Internet access, flashlight, vibrate, audio output settings, etc.

- Dangerous: The phone prompts users to allow or deny

- Camera, microphone, location, contacts, etc.

- Special: Highest risk - must be manually granted in device settings

- BIND_DEVICE_ADMIN: Set passcode, lock device, wipe device

- SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW: Draw on the user’s screen (automatically granted to Play Store apps)

- BIND_ACCESSIBILITY_ADMIN: Automate keystrokes, retrieve window and text content

Google has implemented some protections to mitigate the threat of Android malware. They regularly audit applications submitted to the Play Store for malicious behavior but often fall short. The iRecorder application was uploaded to the Play Store in September 2021 without malicious functionality. The developers added the AhMyth remote access trojan (RAT) in August 2022, which went undetected until May 2023. The app had been downloaded more than 50,000 times during that time.

Google Play Protect is a feature of Google Mobile Services that essentially acts as EDR for Android phones. It performs malware screening for Play Store apps and can remotely scan sideloaded applications. It also helps locate lost devices and remotely wipes the device if needed. However, like any EDR/antivirus, it is often bypassed, especially by less common payloads or new versions of existing malware and obfuscation techniques that Google has yet to create detections for.

iOS Malware

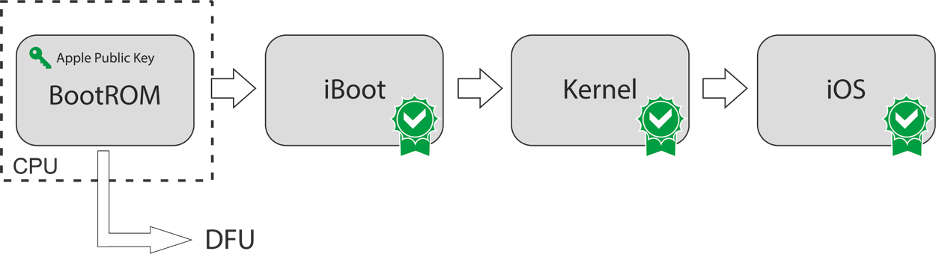

Unlike Android, the standard iOS malware ecosystem is minimal, mainly due to iOS code signing requirements. All code executed on non-jailbroken iPhones must be signed by Apple, including the operating system itself. The BootROM in the CPU contains Apple’s public key, which is used to validate the signature of the bootloader, iBoot engine, and the kernel. The checkm8 vulnerability in the BootROM on Apple chips before A12 allowed skipping signature validation, paving the way for unpatchable, hardware-based jailbreaks on all affected devices.

That same public key verifies the signature of every application downloaded from the Apple App Store, which Apple signs using its private key. Apple performs very strict screening on applications submitted to the App Store, and unlike Google Play, malware is short-lived if it begins behaving maliciously after being accepted. Unlike Android apps, iOS apps cannot remotely download and execute additional libraries since the code is not signed.

Users can only install applications from official Apple repositories or developer or enterprise-signed applications on a non-jailbroken device. Developer certificates are signed by Apple and provided to individuals with an Apple account. Apps signed with the developer certificate are tied to a unique device identifier (UDID), limiting their scope to a specific device. Single device registration makes it impossible to widely distribute a developer-signed application, as an attacker would need to create separate versions for every target device, in addition to the victims needing to manually import the developer profile.

Enterprise-signed applications can spread malware more easily. Apple issues enterprise certificates to registered organizations with more than 100 employees to distribute internal applications on company devices. Apple tightly controls this program and thoroughly vets each participating organization. If Apple detects any wrongdoing, such as sharing internal apps externally or enterprise-signed applications behaving maliciously, Apple can revoke the certificate at any time.

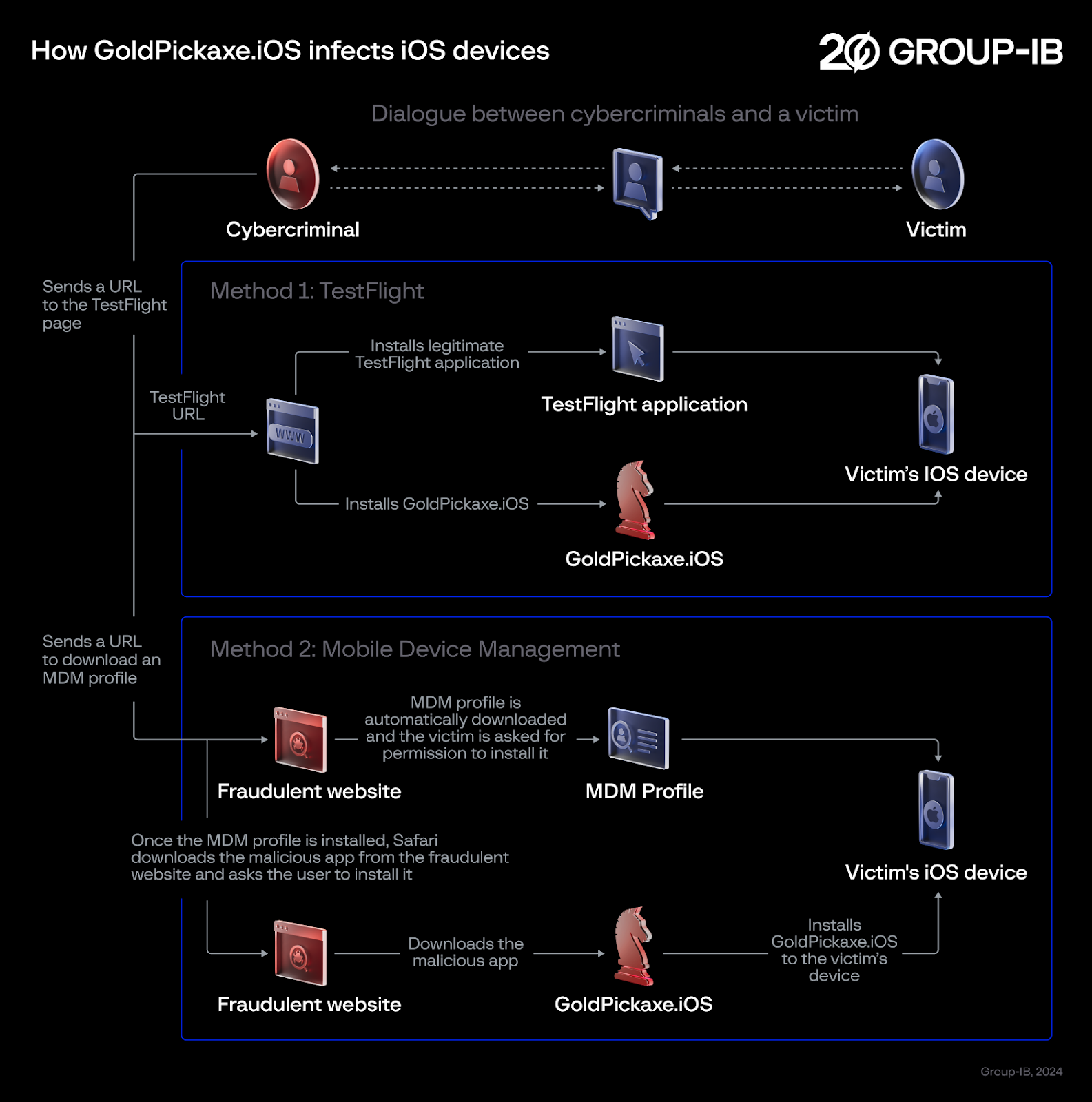

A recent example is a strain of iOS malware tracked by Group-IB, dubbed “GoldPickaxe.iOS” distributed in Vietnam and Thailand. One of its delivery methods is via TestFlight, Apple’s beta testing platform, which has looser vetting processes than the App Store. Victims must accept an invitation to join the attacker’s testing program and install TestFlight. The other installation method is in conjunction with enterprise certificates. Attackers would distribute an enterprise-signed app version and the enterprise profile to install on victim devices. The attackers likely joined the Apple Enterprise Program fraudulently or perhaps stole another organization’s private key.

The GoldPickaxe malware itself, unlike many Android malware apps, is limited in its access. iOS lacks some of the dangerous permissions available to Android applications to request. It masquerades as a government application and asks the user for official documentation and facial recordings. The malware operators use this information to access the victim’s bank accounts. It can also retrieve SMS messages from phone numbers outside the user’s contact list to retrieve MFA codes, which legitimate iOS apps also do to speed up the user login process.

Conclusion

iOS, unlike Android, is a thoroughly locked-down platform. Users do not have full control over the device they own. This makes it much harder to be infected with common malware or to accidentally brick your phone. While it is historically more susceptible to advanced attacks, the average user usually has nothing to worry about and is too boring for an APT to use a zero-day exploit on. For these reasons, iOS is the preferred choice for users who may not be as security conscious, such as teenagers or the elderly.

For average users who are familiar with social engineering and practice good security hygiene, it really doesn’t matter which platform they use. Android is more like owning a pocket-sized PC. Many people own laptops that allow them administrative privileges to install anything they want, including viruses. Android is the same thing - with great power comes great responsibility.

However, for journalists, politicians, freedom fighters, or other individuals potentially targeted by an advanced threat like a government agency, the platform you choose and its configuration matters. For the best protection, externally facing surfaces like SMS/RCS and cellular phone calls should be disabled. Remote attacks often target these services, similar to a web server hosted on the internet. Generally speaking, Android has a better reputation for being harder for nation-states/APTs to hack. I believe open source is generally more secure, which may explain why we see less sophisticated Android hacks than iOS. Few things illustrate this perspective more than the never-ending flood of critical vulnerabilities affecting proprietary “security” appliances like firewalls and VPN gateways that are disclosed every month.

Your country and the government that wants to target you also matter. You may be more protected if you live in a Western country and a country unaligned with Western powers wants to hack your phone. Many exploit development companies that supply to government customers are based in Western countries. While there are instances of customers misusing these products, exploit developers are often subject to export regulations and likely have no desire to sell to adversarial countries anyway. Western adversaries like China, Russia, Iran, etc., must rely on their own R&D efforts.

A device built in Western countries is also probably more secure than one built by Chinese companies, whose government can force them to install backdoors. For this reason, Samsung and Google Pixel phones are generally more reliable than their Chinese competitors like Xiaomi and Oppo. Google Pixel has the added advantage of being designed by the same company that maintains the AOSP, increasing its efficiency at fixing security issues. Unfortunately, these phones aren’t available to everyone, such as citizens of countries where the products are restricted or unavailable.

Even for Western citizens who can purchase and use the latest and greatest Google Pixel or Samsung Galaxy, if a Western power wants to hack your phone, they probably can. While companies may try to resist, the government often compels them to do their bidding, citing national security concerns and legal loopholes. Android may be open source, but many components are not, like hardware drivers and Google Mobile Services. Google can theoretically abuse GMS to backdoor the device. After all, GMS has system-level permissions for installing security patches.

No system is 100% secure and risk-free. Code vulnerabilities will always exist, as will supply chain dependencies and determined threat actors. Such is the never-ending game of cat and mouse in the modern digital world.

References

The inspiration for this blog post comes from SANS SEC575: iOS and Android Application Security Analysis and Penetration Testing, taught by Jeroen Beckers.

- Time Spent Using Smartphones 2024

- Mobile Operating System Market Share Worldwide

- Mobile Operating System Market Share in the United States

- Android Statistics - Top manufacturers

- Architecture of iOS Operating System

- Architecture of the iOS

- Apple security releases

- Android Architecture Overview

- Android Platform Architecture

- Android Kernel Overview

- Everything you need to know about Android’s Project Mainline

- Android Enterprise Device Glossary

- Android Enterprise OEM Glossary

- Google Mobile Services

- GMS certification: A complete guide from requirements to submission

- Is Android Enterprise supported in China?

- AndroidRuntime.cpp

- About the security content of iOS 18.3 and iPadOS 18.3

- About the security content of iOS 18.2 and iPadOS 18.2

- Android Security Bulletin January 2025

- Android Security Bulletin December 2024

- NIST NVD: CVE-2024-49747 Detail

- NIST NVD: CVE-2024-54499 Detail

- Apple nears switch to in-house Bluetooth and Wi-Fi chip for iPhone, smart home, Bloomberg reports

- Operation Triangulation: The last (hardware) mystery

- BLASTPASS - NSO Group iPhone Zero-Click, Zero-Day Exploit Captured in the Wild

- Zero-Day Marketplace Explained: How Zerodium, BugTraq, and Fear contributed to the Rise of the Zero-Day Vulnerability Black Market

- Serbia: Authorities using spyware and Cellebrite forensic extraction tools to hack journalists and activists

- The Qualcomm DSP Driver - Unexpectedly Excavating an Exploit

- Permissions on Android

- Google Play malware clocks up more than 600 million downloads in 2023

- Google Play Protect: On-device Protections

- Analysis and Reproduction of iPhone BootROM Exploit: Checkm8

- App code signing process in iOS, iPadOS, tvOS, watchOS, and visionOS

- Face Off: Group-IB identifies first iOS trojan stealing facial recognition data

- Apple Developer Enterprise Program

- Distributing your app for beta testing and releases